In a recent developer forum I made the rather wild decision to try demonstrate the principles of unit testing via an interactive mobbing session. I came prepared with some simple C# functions based around an Aspnetcore API and said “let’s write the tests together”. The resultant session unfolded not quite how I anticipated, but it was still lively, fun and informative.

The first function I presented was fairly uncontentious – the humble fizzbuzz:

[HttpGet]

[Route("fizzbuzz")]

public string GetFizzBuzz(int i)

{

string str = "";

if (i % 3 == 0)

{

str += "Fizz";

}

if (i % 5 == 0)

{

str += "Buzz";

}

if (str.Length == 0)

{

str = i.ToString();

}

return str;

}

Uncontentious that was, until a bright spark (naming no names) piped up with questions like “Shouldn’t 6 return ‘fizzfizz’?”. Er… moving on…

I gave a brief introduction to writing tests using XUnit following the Arrange/Act/Assert pattern, and we collaboratively came up with the following tests:

[Fact]

public void GetFizzBuzz_FactTest()

{

// Arrange

var input = 1;

// Act

var response = _controller.GetFizzBuzz(input);

// Assert

Assert.Equal("1", response);

}

[Theory]

[InlineData(1, "1")]

[InlineData(2, "2")]

[InlineData(3, "Fizz")]

[InlineData(4, "4")]

[InlineData(5, "Buzz")]

[InlineData(9, "Fizz")]

[InlineData(15, "FizzBuzz")]

public void GetFizzBuzz_TheoryTest(int input, string output)

{

var response = _controller.GetFizzBuzz(input);

Assert.Equal(output, response);

}

So far so good. We had a discussion about the difference between “white box” and “black box” testing (where I nodded sagely and pretended I knew exactly what these terms meant before making the person who mentioned them provide a definition). We agreed that these tests were “white box” testing because we had full access to the source code and new exactly what clauses we wanted to cover with our test cases. With “black box” testing we know nothing about the internals of the function and so might attempt to break it by throwing large integer values at it, or finding out exactly whether we got back “fizzfizz” with an input of 6.

Moving on – I presented a new function which does an unspecified “thing” to a string. It does a bit of error handling and returns an appropriate response depending on whether the thing was successful:

[Produces("application/json")]

[Route("api/[controller]")]

[ApiController]

public class AwesomeController : BaseController

{

private readonly IAwesomeService _awesomeService;

public AwesomeController(IAwesomeService awesomeService)

{

_awesomeService = awesomeService;

}

[HttpGet]

[Route("stringything")]

public ActionResult<string> DoAThingWithAString(

string thingyString)

{

string response;

try

{

response = _awesomeService

.DoAThingWithAString(thingyString);

}

catch (ArgumentException ex)

{

return BadRequest(ex.Message);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

return StatusCode(500, ex.Message);

}

return Ok(response);

}

}

This function is not stand-alone but instead calls a function in a service class, which does a bit of validation and then does the “thing” to the string:

public class AwesomeService : IAwesomeService

{

private readonly IAmazonS3 _amazonS3Client;

public AwesomeService(IAmazonS3 amazonS3Client)

{

_amazonS3Client = amazonS3Client;

}

public string DoAThingWithAString(string thingyString)

{

if (thingyString == null)

{

throw new ArgumentException("Where is the string?");

}

if (thingyString.Any(char.IsDigit))

{

throw new ArgumentException(

@"We don't want your numbers");

}

var evens =

thingyString.Where((item, index) => index % 2 == 0);

var odds =

thingyString.Where((item, index) => index % 2 == 1);

return string.Concat(evens) + string.Concat(odds);

}

}

And now the debates really began. The main point of contention was around the use of mocking. We can write an exhaustive test for the service function to exercise all the if clauses and check that the right exceptions are thrown. But when testing the controller function should we mock the service class or not?

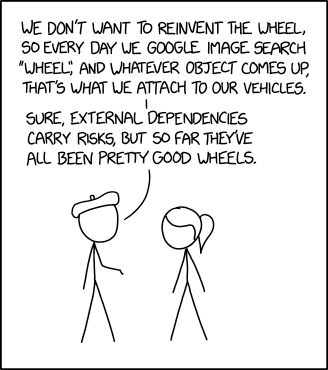

Good arguments were provided for the “mocking” and “not mocking” cases. Some argued that it was easier to write tests for lower level functions, and if you did this then any test failures could be easily pinned down to a specific line of code. Others argued that for simple microservices with a narrow interface it is sufficient to just write tests that call the API, and only mock external services.

Being a personal fan of the mocking approach, and wanting to demonstrate how to do it, I prodded and cajoled the group into writing these tests to cover the exception scenarios:

public class AwesomeControllerTests

{

private readonly AwesomeController _controller;

private readonly Mock<IAwesomeService> _service;

public AwesomeControllerTests()

{

_service = new Mock<IAwesomeService>();

_controller = new AwesomeController(_service.Object);

}

[Fact]

public void DoAThingWithAString_ArgumentException()

{

_service.Setup(x => x.DoAThingWithAString(It.IsAny<string>()))

.Throws(new ArgumentException("boom"));

var response = _controller.DoAThingWithAString("whatever")

.Result;

Assert.IsType<BadRequestObjectResult>(response);

Assert.Equal(400,

((BadRequestObjectResult)response).StatusCode);

Assert.Equal("boom",

((BadRequestObjectResult)response).Value);

}

[Fact]

public void DoAThingWithAString_Exception()

{

_service.Setup(x => x.DoAThingWithAString(It.IsAny<string>()))

.Throws(new Exception("boom"));

var response = _controller.DoAThingWithAString("whatever")

.Result;

Assert.IsType<ObjectResult>(response);

Assert.Equal(500, ((ObjectResult)response).StatusCode);

Assert.Equal("boom", ((ObjectResult)response).Value);

}

}

Before the session descended into actual fisticuffs I rapidly moved on to discuss integration testing. I added a function to my service class that could read a file from S3:

public async Task<object> GetFileFromS3(string bucketName, string key)

{

var obj = await _amazonS3Client.GetObjectAsync(

new GetObjectRequest

{

BucketName = bucketName,

Key = key

});

using var reader = new StreamReader(obj.ResponseStream);

return reader.ReadToEnd();

}

I then added a function to my controller which called this and handled a few types of exception:

[HttpGet]

[Route("getfilefroms3")]

public async Task<ActionResult<object>> GetFile(string bucketName, string key)

{

object response;

try

{

response = await _awesomeService.GetFileFromS3(

bucketName, key);

}

catch (AmazonS3Exception ex)

{

if (ex.Message.Contains("Specified key does not exist") ||

ex.Message.Contains("Specified bucket does not exist"))

{

return NotFound();

}

else if (ex.Message == "Access Denied")

{

return Unauthorized();

}

else

{

return StatusCode(500, ex.Message);

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

return StatusCode(500, ex.Message);

}

return Ok(response);

}

I argued that here we could write a full end-to-end test which read an actual file from an actual S3 bucket and asserted some things on the result. Something like this:

public class AwesomeControllerIntegrationTests :

IClassFixture<WebApplicationFactory<Api.Startup>>

{

private readonly WebApplicationFactory<Api.Startup> _factory;

public AwesomeControllerIntegrationTests(

WebApplicationFactory<Api.Startup> factory)

{

_factory = factory;

}

[Fact]

public async Task GetFileTest()

{

var client = _factory.CreateClient();

var query = HttpUtility.ParseQueryString(string.Empty);

query["bucketName"] = "mybucket";

query["key"] = "mything/thing.xml";

using var response = await client.GetAsync(

$"/api/Awesome/getfilefroms3?{query}");

using var content = response.Content;

var stringResponse = await content.ReadAsStringAsync();

Assert.NotNull(stringResponse);

}

}

At this point I was glad that the forum was presented as a video call because I could detect some people getting distinctly agitated. “Why do you need to call S3 at all?” Well maybe the contents of this file are super mega important and the whole application would fall over into a puddle if it was changed? Maybe there is some process which generates this file on a schedule and we need to test that it is there and contains the things we are expecting it to contain?

But … maybe it is not our job as a developer to care about the contents of this file and it should be some other team entirely who is responsible for checking it has been generated correctly? Fair point…

We then discussed some options for “integration testing” including producing some local instance of AWS, or building a local database in docker and testing against that.

And then we ran out of time. I enjoyed the session and I hope the other participants did too. It remains to be seen whether I will be brave enough to attempt another interactive mobbing session in this manner…